The days leading up to Christmas Break in my Modern Literature class have been spent reading Simon Wiesenthal's The Sunflower, which (and here I don't mean to be disrespectful to a work of literature that powerfully addresses the issues of what is and is not forgivable) is nevertheless about as cheerful in December as a shovel to the groin. So I spent the last day of class in 2010 giving the kids a slideshow of important works of contemporary art that we can compare and contrast to the world we've read. Among other things, we had to take a look at Warhol's soup cans. I mean, why not. They were outraged, just the way Andy would have wanted it. Andy Warhol died in the spring of my senior year of high school, and he was still considered vaguely controversial back then. Hilton Kramer of New Criterion wrote a postmortem that discounted his lasting value. The Times talked about his contribution with its characteristically smug, slightly dismissive air. It's nice to know his soup cans are still pissing people off.

But I was disappointed that among my students his famous line - "In the future everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes" - fell on deaf ears. I suppose that when Andy was proported to have said it, the common reaction among people would probably have been "Everybody? Really?" My students reacted to the latter part of it. "Really?" they seemed to ask. "For only fifteen minutes?" In our time, everybody has the potential to be instantly famous for what seems forever, and everyone is watching.

****

Did Rex Ryan not know this, or did he not care? Regardless, I confess that don't care, but I had to look anyway.

In our culture, the universal, craven appreciation for the fall of others is matched only by our desire to put everything we have and know on display for all to see. These sometimes paradoxical indulgences are a normal corruption of the freedom of information, and they have both recently preyed upon our head coach. I watched about a whole minute of one of Michelle Ryan's foot fetish videos (the one with her feet dangling out of a parked car) and found it about as offensive as Rex Ryan's use of "fuck" as a noun and a gerund, which is not at all. None other than Darrelle Revis spoke in defense of his coach by stating that Rex is at least appreciating his wife in these videos and not, say, his own dong.

The one I watched was actually humorous in a way that is...well, I don't want to use the word charming, but let's just say that it was naively goofy. Michelle Ryan sits, almost napping on a summer day (presumably in Maryland) with her feet (are they pretty? Allow me here to say that I have feet described as essentially ugly by women throughout time, yet I don't know what makes feet beautiful. Hands, yes. But feet? I don't have the eyes for it) dangling out the driver's side window of what looks like an SUV. The camera approaches feet first and then the owner. The voice behind the camera speaks almost as a member of the law enforcement community, with the suggestion that a parked woman brazenly exposing her feet is committing some kind of foul. The woman apologizes. But then the cameraman replies that it's no trouble at all; in fact, he's enjoying the sight of it. Please feel free, ma'am, to keep 'em right where they are. It's almost as if a cop is having to tell a women that she is not wearing her shirt. Except it's her feet.

The voice, as so many people have pointed out, is obviously Rex's. Except it's a different Rex, one whom we don't hear from all that often. It sounds ridiculous to say that when we are exposed to so much of Rex Ryan; I think he makes so much of himself as a means of concealing his own sense of fear. His bluster is exactly the work of a man ill at ease with his looks, his intelligence, his skills - particularly in a market where there are two football teams and no means of escape. The voice on the video, though, is the ur-Rex. His fascinated state trooper is tinged with the slightest Oklahoma drawl. If one did not know better for plainly obvious reasons, then one could almost mistake it for Rex's daddy. I would never have guessed Rex Ryan had a foot thing, but with his murmuring drawl, his weird, sneering look, one could imagine Buddy Ryan having all kinds of hangups.

It was at that point that I had to stop watching. For one thing, I didn't want to watch all the videos because I felt as though I were watching something made by a friend of mine. These are people I know, I thought to myself. Even if they put this out there, I still don't want to know about this. This doesn't make me a good person, just a vaguely normal one. I'm morbidly curious by nature, but I also don't have to see all of a compromising moment to get enough of all I need to know. The Times can look upon Rex Ryan the way Judge Smells does Al Czervik in Caddyshack, as the uncouth and interloping baboon, but the human need to share one's entire personality with the whole world online is exactly what is destroying newspapers. The Times' granny attitude toward the coach, that he is "dumb," may prove to be accurate in reference to this coach in the long run; backing into the playoffs will enable Rex to keep his job another year, but he has yet to produce the team he loftily, delusionally imagines. But what keeps the Old Gray Lady hurtling toward the abyss is its air of superiority about Andy Warhol's open world, warts, feet and all.

A man, a fan, a team, a plan. Through seasons of despair, we discuss every player in New York Jets history. As with life, there is a certain end to our work, though we are never really finished.

Tuesday, December 28, 2010

Saturday, December 18, 2010

NY Jets #22 - Danny Woodhead's Revenge

I wasn't paying attention when Danny Woodhead was waived in September 2010, probably because I believed too firmly, too calmly in a lot of big things and big ideas. The Jets were picked by their own coach to "lead the league in fucking wins." And to be honest, I don't really remember if he was wearing #22 or #83 by then. I know he wore both; I just never believed that when Rex Ryan said he loved Danny Woodhead as much as he did that he would ever let him go, only to be snapped up by the Jets' biggest rival. Danny Woodhead is exactly the spiritual core the Jets lack as they hurtle toward the abyss in the 2010 season. Before the game with the Steelers in Week 15, I predicted that they would lose every remaining game of the season and that Rex Ryan will be fired by year's end. When they beat the Steelers, I felt a brief measure of relief. But we should have kept Danny Woodhead. As a fairly effective rusher way second on the New England Patriots to Benjarvus Green-Ellis, Danny (I find it difficult to refer to a short man by his last name; that's wrong of me, obviously) will finish the year with the Pats and will appear on their roster next year. He will go to the playoffs; he may win a Super Bowl; he will finish better than Rex Ryan. Though he seems like an awfully nice boy, he will have his revenge.

I wasn't paying attention when Danny Woodhead was waived in September 2010, probably because I believed too firmly, too calmly in a lot of big things and big ideas. The Jets were picked by their own coach to "lead the league in fucking wins." And to be honest, I don't really remember if he was wearing #22 or #83 by then. I know he wore both; I just never believed that when Rex Ryan said he loved Danny Woodhead as much as he did that he would ever let him go, only to be snapped up by the Jets' biggest rival. Danny Woodhead is exactly the spiritual core the Jets lack as they hurtle toward the abyss in the 2010 season. Before the game with the Steelers in Week 15, I predicted that they would lose every remaining game of the season and that Rex Ryan will be fired by year's end. When they beat the Steelers, I felt a brief measure of relief. But we should have kept Danny Woodhead. As a fairly effective rusher way second on the New England Patriots to Benjarvus Green-Ellis, Danny (I find it difficult to refer to a short man by his last name; that's wrong of me, obviously) will finish the year with the Pats and will appear on their roster next year. He will go to the playoffs; he may win a Super Bowl; he will finish better than Rex Ryan. Though he seems like an awfully nice boy, he will have his revenge.Danny Woodhead is the talisman the Jets gave away. He's not a premier talent like ones on defense we have given away, like John Abrahams (#'s 94, 56) or James Farrior and Jonathan Vilma (both #51). Imagine a linebacking core like that going against rapist Ben Roethelsberger this weekend. Woodhead is not a shaman. By the looks of it, he is the simple yet talented kid out of Nebraska who tries to sell is own jersey in the big city without a single person recognizing his face. He is exactly what Rex Ryan is not, which is why he might have been magic for a team whose profile has superseded its courage. I talked about his talent when we chatted about #35, which was also one of Danny Woodhead's numbers, just after he was drafted by Mangini, just before he blew out his knee in his first professional training camp. I hadn't been buying the hatred dispensed by New York's snootier outfits this season, with their claims that the Jets' hubris would eventually undo them, but now clearly the haters would appear to have been understating the calamity. Danny Woodhead would never have prevented all of this from happening had he stayed with the Jets; his departure was simply an indication of which the way the wind would blow.

As davidhill points out, though, he left the Jets wearing #27. I have no memory of that, but I believe it. That's how konked out I've been by this season's promises.

****

Do you have a brother like Tank Carter? Tyrone Carter does. Though he played for the Jets in #22 during a single season of 2003, Tyrone has been playing for the Steelers since 2004, and as was widely reported after Super Bowl XL, Tank attended his brother's big game instead showing up to serve a prison sentence of six months. Lucky that the Steelers won because once he was apprehended, Tank's sentence was extended four and a half years. So I ask you again. My brother would probably not request that of me. I'm assuming here that I'm the one going to jail.

****

According to the NFL Players Association, the average career of an NFL player is 3.5 years. As far as I know, only a few American careers are comparable in this sense of their raw attrition. Teaching is comparable. Public school teaching has a burnout rate from the front end of about five years. Number 22 Mike Dennis ended his season with the New York Jets in 1984 after the duration of five seasons in the NFL. So your next rational question is what can Mike Dennis' career teach us about the demands of an average American's professional life? Well might you ask. Well. Might. You. Ask. Or are you better off studying the work of #22 Sean Dykes (no relation to #28 Donald Dykes) whose claim to fame was six games in the strike-ridden 1987 season and, according to the Jets database, "selling Mazdas in the off-season, during his time with the Jets," which in itself is a bit of a paradoxical state of being? No.

Or a viciously cruel state of being. When I played Pee Wee football, I played on a team whose record was 0-6-1. When I played AYSO on Long Island, our soccer team won zero games. My two Little League baseball teams each won one game apiece all season. Was it something I did or said? Was my hangdog look infectious? After all, I was the least effectual member of all of these teams, the player whom the coach looked at with the same disgruntled expression I gave to the kid who told me today that she couldn't answer any of the quiz questions on the chapters of Catcher in the Rye that I had read in class yesterday because she hadn't read the two chapters the two days before before them. Why do I fucking bother? Carl Greenwood played in #22 at cornerback for the New York Jets during the 1995 and 1996 seasons, in which the Jets won all of four football games. He might have asked himself the same question, though that's at least a better record than my years in Long Island sports.

****

A saga involving #24 spilled over onto #22. Ty Law was once a #24, but then wore #22 for the brief period he was brought in for the 2008 season once Jesse Chatman was deactivated for the away Patriots game. Ty Law was always an on-again-off-again prodigal son for Those Of Whom We Do Not Speak. I don't expect Danny Woodhead to return to the Jets anytime soon, but the fierce rivalry between the two teams had its crescendo in Danny Woodhead getting plenty of playing time in the 2010 Tea Party-sized shellacking the Patriots did of the Jets at Foxboro. Activate a rival's former player before the big showdown with the rival. It worked for Danny Woodhead, but Ty Law's career is now officially done. It didn't work in 2008, but then not much did that year.

****

I've been trying to figure out what to say about wide receiver Nick Bruckner, aside from the fact that he was actually from Astoria, Queens. At 5'11", he was a little foreshadowing of Wayne Chrebet, though a little taller. Ah, I know. The reason why we mention him is because he wore #86 in 1983, #83 in 1985 and #22 in 1985 - three numbers in three years. The final change was indicative of a demotion for a wide receiver.

Not unlike Kenny Lewis who, according to the Jets database, wore #24 in 1980 and the #20 in 1981. Then he was #22 in 1983. Is this the fate of special teams, the "Help" of professional football?

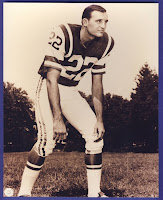

My father always told me that Jim Hudson was the most fiery member of the 1968 team. Dad probably got that idea because Hudson got thrown out of the Heidi Game, which must have meant he was a badass because that is one of the most penalized games in AFL history. In the AFL Championship Game, we see him narrowly miss out on an interception, and he pounds the turf so angrily that he looks like an infuriated adolescent unable to control the connection between his still immature frontal lobe and his fist. But most importantly, #22 Jim Hudson got in front of the pass that should have gone to Jimmy Orr but went instead to Jerry Hill in Super Bowl III. This was, perhaps, the most important defensive play of the most important game in New York Jets history.

My father always told me that Jim Hudson was the most fiery member of the 1968 team. Dad probably got that idea because Hudson got thrown out of the Heidi Game, which must have meant he was a badass because that is one of the most penalized games in AFL history. In the AFL Championship Game, we see him narrowly miss out on an interception, and he pounds the turf so angrily that he looks like an infuriated adolescent unable to control the connection between his still immature frontal lobe and his fist. But most importantly, #22 Jim Hudson got in front of the pass that should have gone to Jimmy Orr but went instead to Jerry Hill in Super Bowl III. This was, perhaps, the most important defensive play of the most important game in New York Jets history.

Sunday, December 12, 2010

NY Jets #22 - Burgess Owens' Revenge

In his rookie year, Erik McMillan emerged as that rare thing in Jets' history, a fairly effective defensive back. He played in #22 for the Jets from 1988 to 1993, the meat and potatoes of the Coslet years. His finest year may have been his rookie one, where he went to the Pro Bowl and lead the AFC in interceptions. There is a long feature 1988 article in the Times by Ira Berkow that identifies Erik as the son of Ernie McMillan, longtime St. Louis football Cardinals great. The article is dated from the Sunday of the Jets' 1988 late-game win of the Giants that guaranteed that my friend Major the Giants fan would have to wear my dirty Jets t-shirt all week. The phrase used to describe Erik in the article was "sometimes explosive," whereas he was described in the Times in 1992 as flatly "out of control." Go ahead. Click on his picture. Looks kind of crazy, doesn't he?

In his rookie year, Erik McMillan emerged as that rare thing in Jets' history, a fairly effective defensive back. He played in #22 for the Jets from 1988 to 1993, the meat and potatoes of the Coslet years. His finest year may have been his rookie one, where he went to the Pro Bowl and lead the AFC in interceptions. There is a long feature 1988 article in the Times by Ira Berkow that identifies Erik as the son of Ernie McMillan, longtime St. Louis football Cardinals great. The article is dated from the Sunday of the Jets' 1988 late-game win of the Giants that guaranteed that my friend Major the Giants fan would have to wear my dirty Jets t-shirt all week. The phrase used to describe Erik in the article was "sometimes explosive," whereas he was described in the Times in 1992 as flatly "out of control." Go ahead. Click on his picture. Looks kind of crazy, doesn't he?But Erik McMillan is used as an object example of how interceptions are misleading. That isn't the case when one changes the shape of the game, but over the course of a season, they are substantially less appealing than the ability to cover your man play after play. According to Deadspin's highly skewed 100 Worst NFL Players of All Time (all time? Think of all the leather-helmeted players who get a free pass), McMillan ranks at #93: "A two-time Pro Bowler with the Jets, McMillan spent most of his time hanging back and waiting for balls to come his way. He was a poor tackler and a worse cover man. Once teams figured that out, he was exposed and, quickly, gone." It's tough to watch other people recognize your own mediocrity after thinking so highly of your skills. To paraphrase the quote misattributed to Euripides, "Those whom the gods wish to destroy, they first call promising." Another misinterpretation has it as "mad." Both of which might apply to McMillan.

When I was a newly minted New York Jets fan in the mid 1970's and Dad went to Jets games at Shea with his brother-in-law, my mother was busy teaching me the finer points of the game. I loved John Riggins because he played red rover with defensive lines, but Mom maintained that a running back's best attributes could be found in his blocking. She showed me a picture of Matt Snell blocking for Namath with fists clenched. That's right. She had pictures of Matt Snell hanging around. Who doesn't?

Sam Gash or Lorenzo Neal. These are big ass fellas who throw their weight in front of everyone and everything in the path of the guy who gets the ball. Amid being the guy who got the ball in New Orleans to being the guy who blocked for Eddie George, Warrick Dunn, Corey Dillon, and (most importantly) LaDainian Tomlinson, Lorenzo Neal also blocked in #22 for Adrian Murrell on the Jets. Here, again, you can see where the Jets are merely the stopover in the greater career.

Burgess Owens was a first round draft choice in 1973 and played for the Jets until 1979. I always wonder if he became expendable after that last season after he injured Pat Leahy in a routine drill in practice. I doubt it, but it made me wonder when I was a hopeful ten year old kid watching his team go through its first transition in his conscious fandom. Owens, #22, was the last player remaining from the 1974 season, my first as a fan. He still had several good years to go, as I would soon discover when his new team - the dread Oakland Raiders - won Super Bowl XV. I had foolishly hyped myself into thinking the Jets would go to the New Orleans that year. The last laugh was when Owens was all over the field in the Superdome, and I had to see it, realizing he was wearing #44 - twice the man he was at #22. I don't know if I've ever hated the Raiders more.

Burgess Owens was a first round draft choice in 1973 and played for the Jets until 1979. I always wonder if he became expendable after that last season after he injured Pat Leahy in a routine drill in practice. I doubt it, but it made me wonder when I was a hopeful ten year old kid watching his team go through its first transition in his conscious fandom. Owens, #22, was the last player remaining from the 1974 season, my first as a fan. He still had several good years to go, as I would soon discover when his new team - the dread Oakland Raiders - won Super Bowl XV. I had foolishly hyped myself into thinking the Jets would go to the New Orleans that year. The last laugh was when Owens was all over the field in the Superdome, and I had to see it, realizing he was wearing #44 - twice the man he was at #22. I don't know if I've ever hated the Raiders more.And Burgess Owens is a Mormon. I'm not supposed to be surprised by that, but I am. Fellow Oakland resident Eldridge Cleaver was, too. I understand the taste of revenge in his going from being a Jet to a Raider, but how odd to convert to a faith that, until recently, didn't really recognize you as an equal citizen in its clergy. But there you go. I know lots of Catholic women who are fine with belonging to a faith that doesn't think they are capable enough of saying Mass. Rooting for a team that wins sporadically makes sense to me, while organized religion leaves me utterly beguiled.

|

| Here comes Damien Robinson's helmet |

Of all the New York Titans, only four started Super Bowl III as Jets - Don Maynard, Bill Mathis, Larry Grantham and Curley Johnson. Who were the other 149 Titans? Well, Leon Riley and Rick Sapienza were two of them - the only Titans who wore #22.

By the way, has anybody seen Jesse Chatman lately - the brief bearer of the #22 for in 2008? As we've discussed previously, Chatman was suspended for violating the NFL's substance policy, but his suspension is up by now (11/15/08). I wouldn't bother asking, except he ran like an artificially enhanced performer all over the Eagles in preseason, and in the 2008 away game against the Pats, Ty Law reappeared #22 instead. Then, Danny Woodhead. I would guess that a even less enhanced Jesse Chatman might be useful at the very least somewhere. Jesse? Jesse?

Three players drafted in the first round of the 1971 NFL draft today have brozne busts in Canton. Can you name them? One of them was drafted by the New York Jets. But we're here to talk about one drafted in the 11th round - a receiver who caught passes at Mississippi thrown from first round draft choice, Archie Manning. We speak of Vern Studdard who played half a season for the Jets in #22 with absolutely no record of his actually playing in any those games.

Eric Thomas and Willie West. Two men at the same position, from different eras in the NFL. West was an AFL All-Star in 1963 for Buffalo and in 1966 for the fledgling Dolphins. Thomas was an All-Pro in 1988. Neither made such appearances for the Jets, although each played in #22 for our team.

There. Number 22. One for the books.

Monday, December 6, 2010

Our 300th Post - Patriots 45 Jets 3

While the Jets were being pummeled by the Patriots in the first half of the Monday Night game, I felt a bit like the drunken washout I resembled when the Jets fell to the AFC Champion-to-be Raiders in the January 2003 playoffs, about five months before I dried out. It was an awful feeling, having nothing else but inebriation to shield me from feelings of cavernous loss. I wouldn’t have cared if the world had caved in. My disappointment was at least tempered by the fact that I eventually had no sense of, well, anything at all. There was no other consolation.

So what was my consolation tonight? Oddly, I found myself listening to the Beatles. From their newly published catalogue on iTunes, I downloaded everything essential gone that's gone missing and stolen over the years, especially Revolver and Hard Day’s Night. The latter became suddenly important to me as the Patriots tagged on a 21-point lead going into halftime. I found Richard Lester’s film A Hard Day’s Night on YouTube and watched it while psychologically checking out of a humiliating blowout. The game played on in the background. We may play in the playoffs and have a revenge, but more than one fellow fan has wondered to me if the Jets will even win another game this year. Ah well. They will finish with a winning record for sure, but I knew the Jets shouldn't have given Danny Woodhead away.

But meanwhile, what came up in the foreground of my view were the Beatles. I first listened to them through my Mom’s stereo as a little kid. She owned A Hard Day’s Night, Rubber Soul, Sgt. Pepper’s, and Abbey Road, her least favorite, a gift from her drugged-out brother-in-law. Each Sunday, while living in Queens and later in North Merrick, my parents would return from Mass, cook breakfast, eat, open the Sunday Times, and listen to two albums – Eileen Farrell’s Puccini Arias and A Hard Day’s Night. The music emanated companionably, twining together like an odd couple not unlike Mom and Dad, themselves – one part classical, one part modern. They insisted on liking both, refusing to choose either at a time when the classical and the modern were entirely separating.

Both albums were recorded before I was born, each a remnant of the early 60’s, back when my parents first fell in love. Though she was more partial to Sinatra than opera, Mom loved Farrell singing “O Mio Babbino Caro” from Gianni Schicci, which I would later hear in the Merchant Ivory film A Room With a View. Dad preferred opera almost exclusively, just as he considered himself a Rockefeller Republican until he met Mom. But in 1964 he found himself voting for Lyndon Johnson and going with Mom to see A Hard Day’s Night in a hot Manhattan theater so crowded with screaming girls as to prohibit a clear sense of exactly what was going on in the movie. But my parents went back again, and despite the fact that they had both skipped over Elvis in their adolescence, they suddenly discovered there and then for themselves the four British men who were already changing the world.

One night, when I was a little boy, and Channel 5 was showing Richard Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night, my parents pulled the RCA black and white into the kitchen for us to watch in its entirety while we ate at the table. I was about six. I may not have been aware of it, but Mom claims that while the music in the film came on, I bounced up and down as I ate. It's an infectious response to the Beatles that I’ve seen in my nieces and my friends’ kids – they’ll all perk up at the sound of Harrison’s Rickenbacker, Starkey’s drums, Lennon’s ooo I need your love, babe and Paul’s Hofner. It's a simple human language of love.

There was once a time when my brother and I could practically do the film from start to finish. Richard Lester presents a colorless picture of an England that I grew up desperately wanting to see for myself someday. When I went to England, I found that The Beatles weren't of anyone's interest, any more than someone on a Memphis street had something to say about Elvis to a Japanese tourist. The Beatles are more an American obsession, but Lester's England was there in England for me to find in its colorless towns and the natives' cheekiness. The movie is more English than the group themselves. The Beatles were already reaching well beyond the simple English trains they run in and out of in A Hard Day's Night, away from the screaming girls from the provincial towns where they play. What makes the movie special is Lester's dialogue.

There are so many great scenes from A Hard Day's Night. In one sequence the film turns toward Ringo’s private sojourn. Having been talked into it by Paul’s Irish grandfather (“a king mixer,” Paul says) Ringo decides to leave the group and go “parading before it’s too late." He's going to find himself as an artist, taking photos of the bleak scenes he encounters. While he walks along a dingy riverside, he collides with a little boy's rolling car tire. The boy is Charlie, aged “10 and two-thirds,” whose face is lashed with dirt. He doesn’t know who Richard Starkey is. To him, Ringo’s just another guy. Charlie says he doesn’t want the tire anymore.

Why? asks Ringo.

“Ah, you can have it. I’m packing it in. It depresses me. It gets on my wick.”

“That’s lovely talk, that is,” says Ringo. “Why aren’t you at school?”

“I’m a deserter.”

“Are you now?

“Yeah, I’ve flung school out.”

“Just you?”

“No. Ginger, Eddie Fallon, and Ding-Dong.”

“Ah,” Ringo says, taking off his camera strap. “Ding-Dong Bell, eh?”

“Yeah, that's right,” Charlie says, nonplussed.

When Charlie asks Ringo why he isn’t at work, the world’s most famous drummer says he’s a deserter, too. Just another dropout.

****

The Jets’ travesty sped its way into the fourth quarter.

I know full well that the Beatles' melodies have kept me aloft through most of my depressing episodes of the past, some real, some imagined. Things like losing at Foxboro 41-7 in 1976, or 55-14 at Foxboro in 1978, or 56-3 in 1979. Or when the first place 10-1 Jets met the Miami Dolphins for a Monday Night Game almost exactly 24 years ago in 1986 and lost 45-3 - and then never won another game during the regular season.

Well, anyway. Whatever the degree to which they are a little too legendary, looming too large in our legend, to turn a phrase from the movie, The Beatles have always existed well beyond the grasp of my own self-inflicted misery and are therefore always a consolation. They sit behind Mom and Dad, and the Jets, right behind Catholicism in the list of the longest looming influences of my childhood. And I’m a little like Charlie tonight. In the film, Ringo eventually abandons his sojourn and gets back with the group in time enough to go onstage for the live show in the film. But what happens to little Charlie? Does he stay a deserter? He throws the tire aside.

It depresses me. It gets on my wick.

****

Where are Ding-Dong Bell and Eddie Fallon. And Ginger?

“Ginger’s mad,” Charlie says. “He says things all the time.”

What things? I wonder.

So what was my consolation tonight? Oddly, I found myself listening to the Beatles. From their newly published catalogue on iTunes, I downloaded everything essential gone that's gone missing and stolen over the years, especially Revolver and Hard Day’s Night. The latter became suddenly important to me as the Patriots tagged on a 21-point lead going into halftime. I found Richard Lester’s film A Hard Day’s Night on YouTube and watched it while psychologically checking out of a humiliating blowout. The game played on in the background. We may play in the playoffs and have a revenge, but more than one fellow fan has wondered to me if the Jets will even win another game this year. Ah well. They will finish with a winning record for sure, but I knew the Jets shouldn't have given Danny Woodhead away.

But meanwhile, what came up in the foreground of my view were the Beatles. I first listened to them through my Mom’s stereo as a little kid. She owned A Hard Day’s Night, Rubber Soul, Sgt. Pepper’s, and Abbey Road, her least favorite, a gift from her drugged-out brother-in-law. Each Sunday, while living in Queens and later in North Merrick, my parents would return from Mass, cook breakfast, eat, open the Sunday Times, and listen to two albums – Eileen Farrell’s Puccini Arias and A Hard Day’s Night. The music emanated companionably, twining together like an odd couple not unlike Mom and Dad, themselves – one part classical, one part modern. They insisted on liking both, refusing to choose either at a time when the classical and the modern were entirely separating.

Both albums were recorded before I was born, each a remnant of the early 60’s, back when my parents first fell in love. Though she was more partial to Sinatra than opera, Mom loved Farrell singing “O Mio Babbino Caro” from Gianni Schicci, which I would later hear in the Merchant Ivory film A Room With a View. Dad preferred opera almost exclusively, just as he considered himself a Rockefeller Republican until he met Mom. But in 1964 he found himself voting for Lyndon Johnson and going with Mom to see A Hard Day’s Night in a hot Manhattan theater so crowded with screaming girls as to prohibit a clear sense of exactly what was going on in the movie. But my parents went back again, and despite the fact that they had both skipped over Elvis in their adolescence, they suddenly discovered there and then for themselves the four British men who were already changing the world.

One night, when I was a little boy, and Channel 5 was showing Richard Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night, my parents pulled the RCA black and white into the kitchen for us to watch in its entirety while we ate at the table. I was about six. I may not have been aware of it, but Mom claims that while the music in the film came on, I bounced up and down as I ate. It's an infectious response to the Beatles that I’ve seen in my nieces and my friends’ kids – they’ll all perk up at the sound of Harrison’s Rickenbacker, Starkey’s drums, Lennon’s ooo I need your love, babe and Paul’s Hofner. It's a simple human language of love.

There was once a time when my brother and I could practically do the film from start to finish. Richard Lester presents a colorless picture of an England that I grew up desperately wanting to see for myself someday. When I went to England, I found that The Beatles weren't of anyone's interest, any more than someone on a Memphis street had something to say about Elvis to a Japanese tourist. The Beatles are more an American obsession, but Lester's England was there in England for me to find in its colorless towns and the natives' cheekiness. The movie is more English than the group themselves. The Beatles were already reaching well beyond the simple English trains they run in and out of in A Hard Day's Night, away from the screaming girls from the provincial towns where they play. What makes the movie special is Lester's dialogue.

There are so many great scenes from A Hard Day's Night. In one sequence the film turns toward Ringo’s private sojourn. Having been talked into it by Paul’s Irish grandfather (“a king mixer,” Paul says) Ringo decides to leave the group and go “parading before it’s too late." He's going to find himself as an artist, taking photos of the bleak scenes he encounters. While he walks along a dingy riverside, he collides with a little boy's rolling car tire. The boy is Charlie, aged “10 and two-thirds,” whose face is lashed with dirt. He doesn’t know who Richard Starkey is. To him, Ringo’s just another guy. Charlie says he doesn’t want the tire anymore.

Why? asks Ringo.

“Ah, you can have it. I’m packing it in. It depresses me. It gets on my wick.”

“That’s lovely talk, that is,” says Ringo. “Why aren’t you at school?”

“I’m a deserter.”

“Are you now?

“Yeah, I’ve flung school out.”

“Just you?”

“No. Ginger, Eddie Fallon, and Ding-Dong.”

“Ah,” Ringo says, taking off his camera strap. “Ding-Dong Bell, eh?”

“Yeah, that's right,” Charlie says, nonplussed.

When Charlie asks Ringo why he isn’t at work, the world’s most famous drummer says he’s a deserter, too. Just another dropout.

****

The Jets’ travesty sped its way into the fourth quarter.

I know full well that the Beatles' melodies have kept me aloft through most of my depressing episodes of the past, some real, some imagined. Things like losing at Foxboro 41-7 in 1976, or 55-14 at Foxboro in 1978, or 56-3 in 1979. Or when the first place 10-1 Jets met the Miami Dolphins for a Monday Night Game almost exactly 24 years ago in 1986 and lost 45-3 - and then never won another game during the regular season.

Well, anyway. Whatever the degree to which they are a little too legendary, looming too large in our legend, to turn a phrase from the movie, The Beatles have always existed well beyond the grasp of my own self-inflicted misery and are therefore always a consolation. They sit behind Mom and Dad, and the Jets, right behind Catholicism in the list of the longest looming influences of my childhood. And I’m a little like Charlie tonight. In the film, Ringo eventually abandons his sojourn and gets back with the group in time enough to go onstage for the live show in the film. But what happens to little Charlie? Does he stay a deserter? He throws the tire aside.

It depresses me. It gets on my wick.

****

Where are Ding-Dong Bell and Eddie Fallon. And Ginger?

“Ginger’s mad,” Charlie says. “He says things all the time.”

What things? I wonder.

Saturday, December 4, 2010

NY Jets #36 - Part 2

Safety Jim Leonhard took a pay cut to move from Baltimore to the Jets and to play for Rex Ryan at the end of the 2008 season. He said that "We decided this was the best situation for me."

Safety Jim Leonhard took a pay cut to move from Baltimore to the Jets and to play for Rex Ryan at the end of the 2008 season. He said that "We decided this was the best situation for me." A pay cut? The best situation? The Jets? When I first read this, I simply appreciated anyone saying that we are the best situation. I felt a little like the experienced teacher who looks with winsome despair at the new recruit who is full of naivete and idealism. Sure, you say that now. A long line starts right there, kid. After all, we are Jets fans. We are never the best situation. But Jim Leonhard has played since then like his is the best situation, and in a matter of a season and a half, he has made people around the NFL believe that he is right. As of this writing, the Jets are tied for first place with New England at 9-2 and are playing for that undisputed place in an upcoming Monday Night game in Foxboro.

But Fate works mysteriously, ironically, cruelly. With days to go to the game, Leonhard broke his leg in a "freak thing" during what was, according to Rex Ryan, the best practice of the week. Eric Smith will replace him, and while Smith is tough, Jim Leonhard is a leader. Symbolically, he represents the heretofore pathos-free hubris of Rex Ryan. He is the man you see depicted above, the small, confident, fearless figure who faces the opposition without concern for either his team's history of failure in December or his opposition's superiority. This is the mental strategy of winners.

And now, as we await a recharged version of the clinical Patriots offense against a derailed Jets defense, I feel happy to at least have come this far. Ryan's reaction to Leonhard's injury was to say, "I feel sorry for Jim, but not for us." That's the attitude I'm talking about. But I've been around too long to believe him. With Jim Leonhard or not, I know the rest of this story, or this one, or this one. If the Jets win this week, it will mark a dramatic change in the narrative I have known for so long. If they beat the Patriots, I will teach all Tuesday in my Namath jersey. And who knows? Maybe I should believe in something bigger than a loser's narcissistic sense of perennial despair. I should try an alternative to that. Maybe I'll try the mental of strategy of winners someday. Meanwhile, I suspect I will not need the Namath jersey.

****

A while ago, you could, for $5 on Ebay, purchase a signed photograph of University of Hawaii Assistant Coach Rich Miano (above) fighting with some unknown persons on the sideline of a recent game. An article on Miano's career (mostly with the Eagles) makes the photo seem even funnier: "He had to fight for a roster spot; he had to fight for playing time. He had to fight for respect. And after the fight was over... Miano raised his arm in victory." OK. Fair enough. Miano is still at Hawaii, but I don't know how much this photo goes for.

But I remember Rich Miano playing defensive back in #36 for the Jets in the 1980's. You can also spend the same amount of money on a signed 1985 photograph of Miano in a 19-6 losing effort against the soon-to-be Super Bowl Champion Bears. Now this I might just buy because it was taken on the day of my first car accident. I was 16 and Christmas shopping; it was freezing but clear and beautiful, and while trying to pull into a parking lot, another 16 year-old Christmas shopper rear-ended me. My parents had just installed an FM radio in my Dad's Chevy - mostly for my benefit - and I was so scared they would think that they had made a mistake in buying it for me because 1) they would assume that I wasn't paying attention to the road because I was trying to turn the dial to just the right place and 2) they would find out that I had been listening to the Jets-Bears game on AM and wonder what the point was of buying the FM radio (with its promises of rock, friends listening to rock in car, friends hooking me up with a girl with whom I could listen to rock in the car so as to shield my mortifying social skills) if I were still listening to AM. What Rich Miano knew about life I also knew about FM radio. I had fought for that thing. Sometimes it feels like you've got to fight for everything. All was well, though. Because I was 16 I underestimated my parents' capacity for understanding. We never did get that dent repaired, though. Or did we? Oh well. I can't remember everything.

But I remember Rich Miano playing defensive back in #36 for the Jets in the 1980's. You can also spend the same amount of money on a signed 1985 photograph of Miano in a 19-6 losing effort against the soon-to-be Super Bowl Champion Bears. Now this I might just buy because it was taken on the day of my first car accident. I was 16 and Christmas shopping; it was freezing but clear and beautiful, and while trying to pull into a parking lot, another 16 year-old Christmas shopper rear-ended me. My parents had just installed an FM radio in my Dad's Chevy - mostly for my benefit - and I was so scared they would think that they had made a mistake in buying it for me because 1) they would assume that I wasn't paying attention to the road because I was trying to turn the dial to just the right place and 2) they would find out that I had been listening to the Jets-Bears game on AM and wonder what the point was of buying the FM radio (with its promises of rock, friends listening to rock in car, friends hooking me up with a girl with whom I could listen to rock in the car so as to shield my mortifying social skills) if I were still listening to AM. What Rich Miano knew about life I also knew about FM radio. I had fought for that thing. Sometimes it feels like you've got to fight for everything. All was well, though. Because I was 16 I underestimated my parents' capacity for understanding. We never did get that dent repaired, though. Or did we? Oh well. I can't remember everything.You can't say much about #36 Joe Fishback's five-game career with the New York Jets, but you can say two things about him. First, he ended his career in Atlanta (where he began) playing in the Georgia Dome for the Dallas Cowboys in Super Bowl Somthingorother against the Bills. This obviously means that he ended his career with a Super Bowl ring; not since I wrote about #24 Johnny Sample have I mentioned a Jet who ended his career with a ring. Secondly, he is the winner of the Booth Lusteg Award Winner for Funniest Sounding Name among the #36s. My apologies to Buddy Crutchfield.

NY Jets #36 - Part 1

As the away game against San Diego began during the Brett Favre season, #36 David Barrett picked off a Philip Rivers pass and brought it back 25 yards for a touchdown - the only touchdown of his career. It was the Jets' first score of the game, and it seemed as though we were beginning the game in exactly the way we needed. However, it was a mirage. The Jets lost the game by more than two touchdowns, and though it was wonderful to see the normally bellicose Rivers seem flustered by Barrett's pickoff, the fact is that the badder guy won in the end. Brett Favre's energetic high fives for the defense as they came off the field were a mirage, too. Brett never bonded with us; he never really cared for anyone other than Jenn Sterger and some assorted Jets employees who were repulsed by his advances. David Barrett was injured for most of the remainder of the 2008 season and was released even before Rex Ryan was brought in to coach. He had a fairly good five seasons with us and that, my friends, is all I'm going to say.

As the away game against San Diego began during the Brett Favre season, #36 David Barrett picked off a Philip Rivers pass and brought it back 25 yards for a touchdown - the only touchdown of his career. It was the Jets' first score of the game, and it seemed as though we were beginning the game in exactly the way we needed. However, it was a mirage. The Jets lost the game by more than two touchdowns, and though it was wonderful to see the normally bellicose Rivers seem flustered by Barrett's pickoff, the fact is that the badder guy won in the end. Brett Favre's energetic high fives for the defense as they came off the field were a mirage, too. Brett never bonded with us; he never really cared for anyone other than Jenn Sterger and some assorted Jets employees who were repulsed by his advances. David Barrett was injured for most of the remainder of the 2008 season and was released even before Rex Ryan was brought in to coach. He had a fairly good five seasons with us and that, my friends, is all I'm going to say.****

Wellington Nathaniel Crutchfield, III goes by "Buddy," and he was a Jetskin, having come over from Washington to the Jets from 1998 to 1999. According to the less than meticulous records of professional football, he made one tackle in his one season with the Jets in #36. In an entirely unrelated piece of information, I once saw blues piano player Jimmy Crutchfield, a local St. Louis legend, and his band play a concert for a group of East St. Louis, IL transitional high school students whose school resembled something out of a third world shanty. After playing for an hour, Crutchfield, a thin, angular man whispered, "One more, one more. Then let's get the hell out of here." I recall that it was rather amusing.

It's not often that I include hijacked snapshots of our Jets Among Men in uniforms other than the green and white. But in this case, from Corbis comes this remarkable 1973 picture (above) of #36 Bob Gresham - who played behind several other Jets running backs in 1975 and '76 - facing insurmountable odds. Playing for the Houston Oilers at the time, Gresham is about to be hit on both sides by the old and new Monsters of Midway - Dick Butkus and Wally Chambers, respectively. In other words, he is about to be plowed. He knows it, surely. In a moment, his vision will be blurred not just by the heavy blue-black of home uniforms but by the shattering, almost noiseless explosion that will take place in his head after these two linebackers hit him. Who knows - maybe even Butkus and Chambers will have some fragment of the experience too, so powerful and terminal do the impending hits seem in this frozen moment of portent.

I feel like Bob Gresham. It's not just my usual paranoia. Sometimes it just feels like the walls are closing in and you're about to be hit by two enormous men who are trained to knock people out of the game, and you're just little Bob Gresham. You come to work, you work hard, you gain your little 400-500 yards in a good season, running off of 2nd and 5, usually. But now you are about to meet one of the hits that will shorten your career and maybe even set you back a little. Here it comes.

****

"Most people believe 1972 was Steve Harkey 's best year." I love when I go to sites like armchairgm.com and encounter such appraisals. It was his best year, especially because running back Steve Harkey #36 gained 129 yards for the Jets that year, 67 more than he gained the previous one. If you look at how running backs start out, I guess you could say that Harkey was on his way to becoming another Bob Gresham, destined to someday be pummeled by a Hall of Fame linebacker or two. But instead, Harkey's career stops after '72, the rest is silence, and all that there is to find in the Jets' Yearbook is the following achievement: "Paved the way for a pair of George Nock TD runs in Week 3 14-10 win over MIA." Paved the way for George Nock. If that's all that you can leave behind, then so be it. You can meet George in #37.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)